Educators who run U.S. schools aren’t a diverse group. Almost 80 percent of the nation’s 90,000 principals are white. Only 11 percent are Black and 9 percent are Latino, according to federal data. That doesn’t come close to reflecting the demographics of the nation’s 50 million public schoolchildren who are 46 percent white, 15 percent Black, 28 percent Latino and 6 percent Asian.

This principal-student mismatch matters for a lot of reasons. For one, researchers have documented that Black principals are often better at attracting and retaining Black teachers. That can reduce teacher turnover at schools in Black communities, where many classrooms are staffed by young, inexperienced teachers who are constantly coming and going, which leads to low student achievement. There’s also evidence that Black teachers are better at recognizing giftedness in Black students and helping more Black students excel academically. Part of the solution to fixing high poverty city schools and closing the Black-white achievement gap may be to hire more Black principals.

Apparently, however, Black principal candidates remain at a distinct disadvantage. A new Texas study, published June 2020 in the peer-reviewed journal of the American Educational Research Association AERA Open found that Black principal candidates were 18 percent less likely to be promoted to principal than equally qualified whites. The study tracked a group of 4,700 assistant principals, who constitute the main recruiting ground for principals, from 2001 to 2017 in Texas. All of them had master’s degrees and state certificates that qualified them to be principals. Two thousand of these assistant principals were promoted to principal. But just over 240 — or only 35 percent of the 690 Black candidates — were actually promoted. Sixty-five percent of the Black candidates in the pool were not promoted. The chances of getting promoted were much higher for the 2,800 white candidates. Forty-five percent of them became principals. The 18 percent disadvantage for Black candidates was calculated after controlling for education, years of experience, type of school (elementary, middle or high school) and location (city, suburb or rural area).

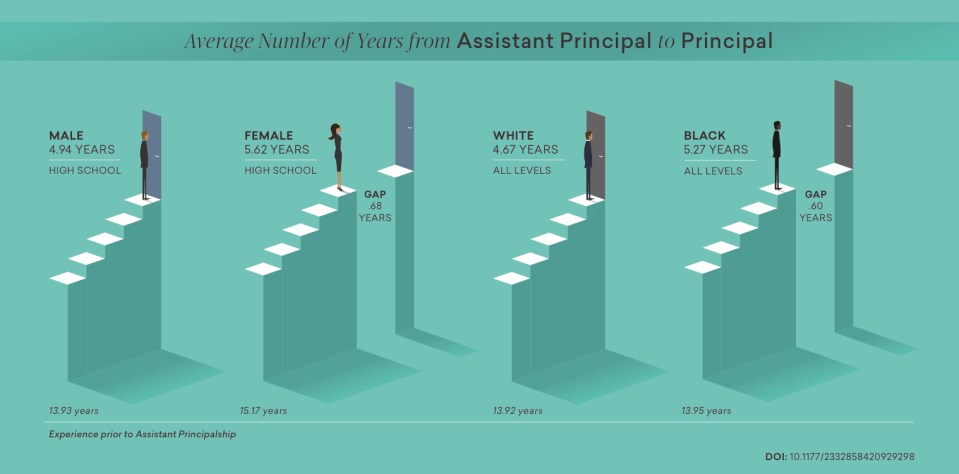

Not only was the Black rate of promotion lower but Black candidates who were promoted also had to wait longer to become principals. White assistant principals were promoted after an average of 4.67 years in the job. The average time for Black assistant principals who were promoted was 5.27 years, seven months longer.

“Diversity does exist in the leadership pipeline,” said Sarah Guthery, a co-author of the study and an assistant education professor at Texas A&M University – Commerce, “but it tends to squeeze out women and Black candidates much earlier than studies of school leadership usually capture.”

The researchers tracked Texas because they had access to the state’s data but the state is not an egregious example of inequity. On the contrary, Texas schools are known for having a more diverse leadership than most other states. In 2018-19, almost 14 percent of the state’s 8,500 school principals were Black, 24 percent were Latino and 60 percent were white. Indeed, there’s a higher proportion of Black principals (14 percent) than there are Black students in the public schools (13 percent of Texas’s 5.4 million public school students).

So the racial discrimination problem among Texas school leaders is complex. There’s an equitable proportion of Black principals but it’s still much harder for qualified Black educators who are in the leadership pipeline to become a principal than white ones.

The grooming and hiring of principals is inherently a subjective and political process that varies from school to school. In theory, district superintendents do the hiring. But sometimes an outgoing principal has a strong influence in tapping his successor. Other times school boards and community sentiment hold sway.

The researchers found a different result when they looked at the Latino principal pipeline. Latino educators had the same chance of becoming a principal and tended to wait the same number of years for the promotion as their non-Hispanic white peers. There’s no evidence of anti-Latino discrimination in principal promotion in this study. The authors suspected that Texas might be unusual because there is a huge demand for leaders with bilingual skills and experience in teaching English as a second language.

There remains a giant gap in the proportion of Latino principals (24 percent) compared with the proportion of Latino students (52 percent). The state would need to hire far more Latino principals to close that gap.

In other words, the inequities faced by Black and Latino educators are mirror images of each other. Black educators have an equitable share of principal positions but face discrimination in promotion. Latino educators are equitably promoted but underrepresented overall.

The promotion of women followed yet another pattern, the researchers found. Women had the same chance of being promoted to principal as men do but their promotions were delayed. Women, on average, had to work eight months longer than men as assistant principals before being promoted. And women had over a year or more teaching experience, on average, before being promoted to assistant principal.

Women account for 65 percent of Texas’s principals, which seems more than fair. But three fourths of all teachers are women, both nationally and in Texas, increasing the competition among women.

“If you’re looking at either the teacher corps or the assistant principals, this is a group of instructors who have worked hard, who have the qualifications, and who are not considered in the same way as their male peers for this promotion,” said Lauren Bailes, who co-authored the study along with Guthery.

Women were also much less likely to get promoted to principal at high schools, the authors found. High school principal positions are a traditional pathway to district superintendent. So keeping women principals at the elementary school level also diminishes their chances at rising to the very top posts in education leadership.

Bailes’s advice to both females and teachers of color who aspire to become principals is to tell others about their ambitions early in their careers. “We want to be careful about saying this is the responsibility of the marginalized group to fix,” said Bailes, “but there is an advantage to being assertive about your career aspirations and putting yourself forward for leadership.”

Bailes also hopes that school districts and state education departments around the country will replicate this study in their communities. That way, they can pinpoint when and how talented educators are getting eliminated from the principal pipeline and begin to address the problems.

Ultimately, these hiring decisions are tough ones. Communities will need to decide whether they want a principal corps that reflects the current teaching profession and is fair to the individual candidates who happen to be in the hiring pool at that moment or whether they want a principal corps that reflects the racial, ethnic and gender composition of the students they serve. It’s often not possible to achieve both goals at once.

This story about Black principals was written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

To Whom It May Concern:

I am a black male who is currently considering pursuing a Master’s in Education in Educational Administration and I must say that this article is discouraging. It is likely true, but disheartening all at the same time. It was my hope that academia would help to inoculate me from the classicism and discrimination which is sadly entrenched in American society. After all, it is a sad feeling knowing that even if you do the right things that you start off at a distinct disadvantage simply because you of your race or sex. It is demoralizing. I liken it to starting a race with the knowledge that a judge has already set the limits of what you are allowed to accomplish.